Last Friday, inspired in part by the emphasis on gin in Graham Chapman’s fictional autobiography, I poured a glass of the Fainting Goat’s very fine emulsion and put on a Charlize Theron film called Atomic Blonde, based on a graphic novel series from Oni Press, which I have not read.

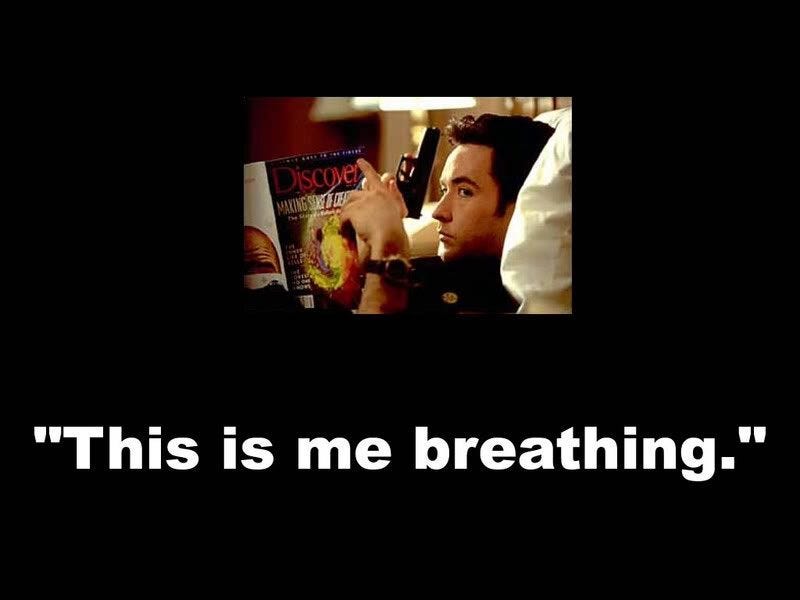

I enjoyed the movie, and not just because of the darkly nostalgic 80s soundtrack, a feature shared with another all-time favorite, Grosse Pointe Blank.

In both films, when things get violent, there’s no glossing over the blood and brutality. That resonates, strongly.

But I also totally agree with the much-better-informed-than-me Ken Klippenstein when he says the following, which also relates to this week’s chapter of the innovation book, below.

Hollywood depicts CIA employees as James Bond spies and action people but the vast majority of its employees are admin, technical, security, and logistics specialists, more even than actual “analysts.”

I revisit this theme of the ordinariness of the intelligence community frequently on this newsletter because I think the mystique they enjoy in the popular imagination is unhealthy.

I liked the setting, too. Berlin, 1989, just as the Wall was about to come down. I have a little chunk of Communist concrete around here somewhere, a gift from a world-traveling girl I once knew.

What I don’t quite understand is the Blonde’s obsession with immersing herself in ice water. As far as I can tell, Wim Hof did not become famous until later, though the general practice of deliberate cold exposure goes back hundreds of years, at least among some lineages of Tibetan monks. Serious research didn’t start on Hof’s “method” until 2007.

On The Brink of Utopia

We’ve previously discussed the Introduction, Chapter 1, and Chapter 2.

chapter 3: The Possessed

This is some attempt to lay out the personality of the “HiPos,” those with a high potential for radical innovation. According to the authors, there are lots of anecdotes about discoveries, but little systematic study of how they occur, in part because they are unpredictable.

Those who make innovative leaps, however, usually show high levels of five additional personality traits or behaviors:

1. Early specialization: an interest, barely comprehensible to others, in a specialized area, sometimes bordering on manic obsession

2. Grit: an unusually high level of tenacity and resilience in the face of setbacks, combined with steadfast independence of mind in response to criticism or even ostracism

3. [Openness: sharing your own knowledge and absorbing interesting ideas] 1

4. The ability to inspire and empower: to transmit their own enthusiasm to others and to build and lead teams without descending into micromanagement

5. Having an impact: the desire for their own work to actually have an impact

Their prototype for this HiPo pentad of traits is the relatively unknown fungus researcher Akira Endo, who discovered the first natural cholesterol-busting statin compound in the 1970s. He worked for a Japanese company called Sankyo and did not win the Nobel or make any money off his discovery.

They pick Endo in part because they are trying to push back against Thomas Carlyle’s Great Man theory of history, which still has a deep hold on western consciousness, especially in the world of business. Steve Jobs? Bill Gates? Elon Musk? All dudes, capturing all the press. Who out there has heard of Gwynne Shotwell, who actually runs SpaceX?

As President and COO of SpaceX, Gwynne Shotwell is responsible for day-to-day operations and for managing all customer and strategic relations to support company growth.

Some of their psychogram traits are obviously chosen because they want to increase the profile and opportunities for women within the leaky innovator pipeline. Great, all for that.

But I think our authors don’t go far enough. Despite their protests, they seem to accept that innovators are special people, and that since successful innovators are rare, they must be even more special. They locate the cause of their effect inside the individual; for them, one key to more innovation is finding more of those people. I argue that their traits are certainly not sufficient; they may not even be necessary.

Talent vs Luck

A 2018 economics paper, which later won the IgNobel prize, was called Talent vs. Luck: the Role of Randomness in Success and Failure. In that paper, the three authors — Pluchino, Biondo, and Rapisarda — did simulations showing that talented people rarely end up on the top of the income distribution, because opportunities for wealth happen randomly and there are a lot more mediocre people available to be hit by those opportunities. Yes, talented people had a higher probability of benefiting, but the effects of luck could easily overwhelm talent.

There is more recent work out there on this question, fleshing out and pushing back, and I could return to that if there’s interest.

At the end of that paper, the 3 Italian Amigos did some policy work, pointing out that the biggest bang per buck was to share the grant money out to as many innovators as possible. Trying to pick winners, to beat the market, didn’t work as well.

Cheaters Often Prosper, for a while

Another Substacker introduced me to an academic fraud scandal I hadn’t heard about.

At first I assumed that “Rochester University” was in Britain, or maybe Minnesota, but no, it was in fact the University of Rochester, where I got my PhD.

And a few months ago, I heard from a fellow alum that one of our classmates had gotten busted, not just for fraud, but for obstruction.

I mention these sad cases in this context because we assume that incentives matter. We assume that bigger and more unequal prizes are more worth working for, and more worth cheating for. It seems obvious. Proving it has turned out to be surprisingly difficult.

First of all, when there is an opportunity to cheat we do not find that individuals increase their effort under competition as commonly assumed and empirically found in some experiments.

Pluchino et al 2018 did not examine cheating. Our Brink authors at one point in another chapter mention Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos but don’t give it much space.

Finally, Horrible Bubbles

Another thing the authors haven’t spent much time on is something science fiction really emphasizes, and that is the downsides of innovation. There are a lot of truly terrible ideas out there, like importing hippos to control invasive water hyacinths.

From a more detailed history:

“This animal, homely as a steam-roller, [is] the embodiment of salvation,” it wrote. “Peace, plenty, and contentment lie before us; and a new life, with new experiences, new opportunities, new vigor, new romance, folded in that golden future when the meadows and the bayous of our Southern lands shall swarm with herds of hippopotami.”

Just replace hippo with AI, and there you go.

Also gunslinging hippo space pirates, not a good idea. Spelljammer in general, really.

Though, to be fair, I did really like Tawaret from Moon Knight. I like this super-creepy Baba Yaga version even better.

I honestly don’t know much about the Egyptian pantheon, beyond ibis-headed Thoth from Arden Vul. I saw a good documentary about cat-headed Bastet, which sparked some ideas for a potential story.

Next week, something completely different.

This is misprinted in the e-book; I took the definition from later in the chapter.

Much more on creating scientists and innovators, hundreds of years ago.

https://substack.com/home/post/p-150296457

Apparently Japanese monks also engage in cold water purifications they call mizugori. American Shinzen Young describes these in detail. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lq1IL_DnC98