I read a lot of books. I don’t finish all of them. I don’t talk about all of them here. Sometimes I just drop a Note or a comment on another Substack. Sometimes I add comments to my own posts, after the fact, when they seem relevant.

This week’s issue is a follow-up to last week’s Science Policy Bootcamp, where I worked with a pair of young science professionals to develop a proposal around using psychedelics to treat opioid addiction. Back in the 50s, medics were very excited about this possibility. The guy who founded Alcholics Anonymous, Bill Wilson, said publicly that LSD had cured his depression, which 20 years of sobriety had not. In fact, he got the idea for AA from an earlier dose of a much more toxic hallucinogen, belladonna (aka deadly nightshade), a Eurasian plant which contains half a dozen psychoactive substances. These facts were highly inconvenient for AA’s tribal practices and marketing, which relied on complete abstinence.

“As these members saw it, Bill’s seeking outside help was tantamount to saying the A.A. program didn’t work.”

And yet AA was quite progressive for its time.

In the 1930s, alcoholics were seen as fundamentally weak sinners beyond redemption. When A.A. was founded in 1935, the founders argued that alcoholism “is an illness which only a spiritual experience will conquer.” While many now argue science doesn’t support the idea that addiction is a disease and that this concept stigmatizes people with addiction, back then calling alcoholism a disease was radical and compassionate; it was an affliction rooted in biology as opposed to morality, and it was possible to recover.

There’s an Oxford House living their under-the-radar lives not too far from my place in Greensboro. I always wondered why the name Oxford House, and I’m now wondering if it’s a nod to the evangelical Christian Oxford Group that inspired AA.

Anyway, I had always assumed that much of the resistance to witchy plant medicines was due to Christianity. But, like with anything else in the 20th century, it turns out that you can, without irony,

Blame the Nazis!

Any student of psychedelic history knows that LSD was discovered in Switzerland in the 1930s by chemist Albert Hoffman. I didn’t know that the company he worked for, Sandoz, was mostly a paint company at that point and didn’t become a majority pharmaceutical company until well after World War 2. One of the first blockbuster psychiatric medicines, thorazine, was actually first made by the paint division.

Norman Ohler previously wrote about the Nazis’ drug use in Blitzed, where he focused mostly on methamphetamine. This book is instead about how the Nazis had access to LSD years before the Allied countries heard about it, and like every other thing they got their hands on, tried to turn it into a weapon. They used it in the concentration camps. They used it during interrogations.

It was a German, the guy who classified schizophrenia as dementia praecox, Emil Kraepelin, who first suggested in 1883 that mental illnesses should be considered through a biochemical lens rather than the electrical or spiritual or psychological lenses popular at the time. Pre-Einstein, people assumed matter and energy were entirely separate, echoing the traditional mind / body split I wrote about here.

The Swiss were supposedly neutral during the war, but Sandoz was perfectly happy to take the Nazis’ money, and some of the individual scientists profiled in the book were perfectly happy to exploit escaping Jews with exclusive and abusive IP agreements, as well as buying up their personal art collections at bargain-basement prices. Ironically, this was essentially what the US did to Nazi scientists after the war, protecting them from the Nuremberg trials but putting them to work in Cold War projects, detailed in Annie Jacobsen’s book Operation Paperclip and later a documentary. This research into psychological weapons tainted everything that came after. Because of the built-in excuse that Well, the Russians are doing the same thing, but worse, many researchers felt free to completely ignore the Nuremberg Code that their own colleagues had just written.

The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.

An especially damnable hypocrite was Ewen Cameron, who was at Nuremberg, who interrogated Rudolf Hess, and who apparently learned nothing from those experiences. From his multiple posts as the president of American, Canadian, and World psychiatric associations he ran some of the most horrific experiments ever done on the human psyche, permanently damaging patients who came to him for help, while charging them for the service.1

The documentary Eminent Monsters from the BBC draws direct lines from this work to Baghram Air Force base in Iraq and to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. Their techniques were Cameron’s techniques, updated and expanded to include Arabic cultural vulnerabilities, like nakedness and fear of dogs. And then they started to influence pop culture, long before 24 but really celebrated there.

24 expressed and amplified American paranoia.

This is homoerotic torture porn, widescreen.

And it’s inaccurate, because in 24, torture works, repeatedly, reliably. This is a case of dueling tropes within pop culture.

Basically, torture doesn’t work on heroes, like Napoleon Solo on the reboot of the Man from U.N.C.L.E. I happened to watch last night, but it does work on criminals, who are all (to quote Batman) a superstitious, cowardly lot.

But Back to the Book

A new bit to me was the existence of the Narcotic Farm in Lexington, Kentucky, originally a posh rehab resort for celebrities and a high-minded research institute, later stuffed to the rafters with addicts as the drug laws became more and more punitive.

vitual museum exhibit https://kyhi.org/other/u-s-narcotic-farm/

book / doc http://narcoticfarm.com/t2_story.html

According to Ohler, patients (mostly black) were bribed with the very substance they were there to get free of (heroin, very pure) to participate in ridiculous experiments where they might spend up to eleven weeks tripping. Just to be completely clear, these are definitely not the sort of experiments I was advocating for last week.

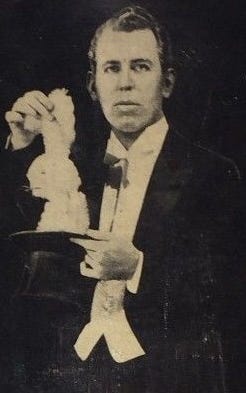

I had also never heard that the spooks hired a magician, John Mulholland, to teach them sleight-of-hand.

So the CIA was basically a D&D thieves’ guild. Or an assassin’s guild, if they did in fact murder JFK for trying LSD, as Ohler hints but doesn’t state openly, and later his “friend” Mary Pinchot, for possibly supplying the drug to him.

Meanwhile, Sandoz was on a parallel track, racing to turn LSD into a medicine, and losing that race when their outsourced R&D program — essentially giving it to any intelligence agency or researcher who asked nicely — blew up in their faces. Psychedelics escaped the lab and became party drugs. People refused to go to Vietnam, in part because these drugs had opened them to the possibility that their government was lying to them (which it definitely was, on multiple levels). A quote from Nixon’s advisor John Ehrlichmann:

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

Ohler covers the Elvis visit to the White House, but not Johnny Cash’s less ass-kissy interactions with Nixon, documented in Tricky Dick and the Man in Black.

The epilogue of the book touches on the current psychedelic renaissance started in Switzerland in the early 1990s and now in cautious trials at universities here. People are again very optimistic about PTSD, anxiety, depresssion — even addiction. Ohler also found some very preliminary work on dementia. He was encouraged enough to try it with his own mother.

With her permission, of course.

On the Brink of Utopia, chapter 2

After a couple weeks doing other things, we return to the topic of innovation and how to foster it. We’ve looked at the Preface and chapter 1 previously.

chapter 2: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Innovation

Any attempt to define technological progress necessarily involves skating on thin ice. What does “better” mean, and for whom and in what sociotechnical context, taking into account any negative consequences and undesirable side effects? And which consequences should be identified as negative, and how can they be quantified? Any attempt must be based on criteria drawn from a framework of values.

Silicon Valley’s values clearly suck. They are openly based on maximizing profit through monopoly, as laid out in the book and as continuously and ably followed by Matt Stoller over at BIG here on Substack.

These authors put forward the UN’s SDGs as a sensible set of values, at a broad societal level.

They bring Maslow’s hierarchy in at a more granular level, hoping to evaluate individual innovations and their costs and benefits for individual humans. This part of the chapter seems under-developed to me. I see the basic idea, but there’s nothing as to how to implement it, just this vaguely suggestive picture.

Then they shift gears to saying that we need to be more aggressive and experiment harder (again, without saying how), based on some ugly examples like thalidomide’s birth defects leading pharmaceutical companies to being too conservative. I can think of some easy counter-examples, like Purdue Pharma and the opioid epidemic from last week’s issue.

So far they haven’t mentioned anything about simulation as a way of testing out technological or social innovations before releasing them into the wild. The beauty of simulation is that you have to lay out your assumptions, and you can change them (transparently, of course). You can do a sensitivity analysis to see which parameters of the model have the largest effects with the smallest changes. This goes beyond financial storytelling.

I did find their punny term exnovation interesting and potentially useful.

Innovation research uses the term “exnovation” to describe the phasing out of technologies that in retrospect turn out to be harmful.

This is a broader term for a process that might end with technologies being outlawed, like genetic engineering of humans and AI in the Star Trek franchise (at least inside the Federation). Getting a law enacted is only one of many levers of policy, though.

Leveraging Substack

Coincidentally, a couple of other perspectives from my Substack reading this week. From this week’s Experimental History, “Good Ideas Don’t Need Bayonets.”

They seem to believe in the authoritarian school of social change: the only way to create a better world is for a strong central actor to force it on everybody else. They don’t think of this as tyranny, of course. They think of it as doing the right thing. And if a thing is right, well, duh, you should make people do it!

But this assumption gets the order of operations wrong. Power is not awarded to truth; power comes from truth. Believing true things ultimately makes you better at persuading people and manipulating reality, and believing untrue things does the opposite. The best ideas don’t need bayonets.

Adam mentions Lysenko and Soviet genetics as examples of bad ideas that failed and failed bigger, with more and nastier consequences, because they were forced on society politically rather than competing in the evidence-based scientific market of ideas. They were bubbles that were inflated artificially so that they got really big before they popped.

I will pile on with a particularly horrifying example from a documentary called Cannibal Island, where 6,000 “social undesirables” purged from Russian cities were dumped on an undeveloped marshy island in the middle of a Siberian river. Giving the cops quotas for deportations, with no trials for quality control, was a predictably bad idea that led to innocent people being arrested for no reason. And because it was a remote area with no oversight, things got really bad before the few survivors were evacuated to other, better gulags.

Our Brink authors describe “foi gras startups,” companies that grow not from revenue but from investor cash. As soon as the company drives its revenue-based competitors out of business, the investors exit and cut off that flow of cash, and the surge pricing begins.

There are now a lot of efforts to kick-start real innovation. Here’s just one example that jumped out of my Substack feed at me.

And here’s another one, more local.

In evolutionary terms, these are all efforts to increase variation. There are few efforts to get rid of bad ideas, what our authors above called exnovation and what evolutionists call selection. And even fewer efforts to maintain proven good ideas, what evolutionists call inheritance. All three are required for a system to evolve. You can read / listen to much more about this at the Podcast link in the masthead above.

There’s a lot of stuff out there on this period, but for my money one of the most entertaining is an audio series called Welcome to Mars by Ken Hollings and Simon Jones, which includes a lot of pop culture context swirling around all the official secrets and scandals.

And this, which is a link I would never have come up with on my own.

https://harpers.org/archive/2024/09/the-new-age-bible-sheila-heti-a-course-in-miracles/

stumbled across this today

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-soviet-union-s-desperate-efforts-at-mind-control