The concept actually originated with Coleridge, long before speculative fiction was a named and recognized umbrella for the multiple genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. Coleridge said that it was a conscious act, a choice to suspend critical thinking, on the part of the audience. Tolkien apparently pushed back on that idea, saying that if the author had done a sufficient job of building a secondary world, buy-in would be a natural (and involuntary / unconscious?) consequence. As I understand it, which is imperfectly. Feel free to correct me.

I haven’t read back past Lord Dunsany, but a local librarian (the same one who ran the brief campaign where I played Glenwood Grassland)

is now running a High Fantasy reading group, starting with George MacDonald’s Phantastes (1858), which seems to have been quite influential. I’m listening to a LibreVox recording. I’ll let you know how that goes.

The concept is never named as such, but it’s a central element in a delightful little sci-fi film festival flick from New Zealand that I caught on Tubi called This Giant Paper-Mache Boulder is Actually Really Heavy, billed as “a high-stakes adventure in a low-budget universe.”

People get literally captured by their enthusiasm and need for escape. In the film, it’s not a conscious decision; slipping into character is something that happens to them when they’re stressed or not paying attention (which is surprisingly close to how Buddhists think about the issue of delusion).

The arising of these feelings may be outside our control—we don’t choose to be angry, for instance. But recognizing how greed, hatred, and delusion cause tremendous harm in the world can help us learn to manage them.

Which, of course, leads us back to QAnon and cults in general. Sigh.

Sigh, for Sigh-ence!

Possibly my favorite undergraduate class at UK was ENG 374, American Folklore. This way of studying culture started in linguistics. People began collecting words and phrases from different languages and comparing them to one another, like naturalists were collecting and comparing the features of plants, animals, rocks, clouds. Once we had microscopes, the same process started with cells. Genes would have to wait for technology to catch up until the middle of the 20th century, and genomics — the comparing of genetic libraries across bodies and species — is just getting going now.

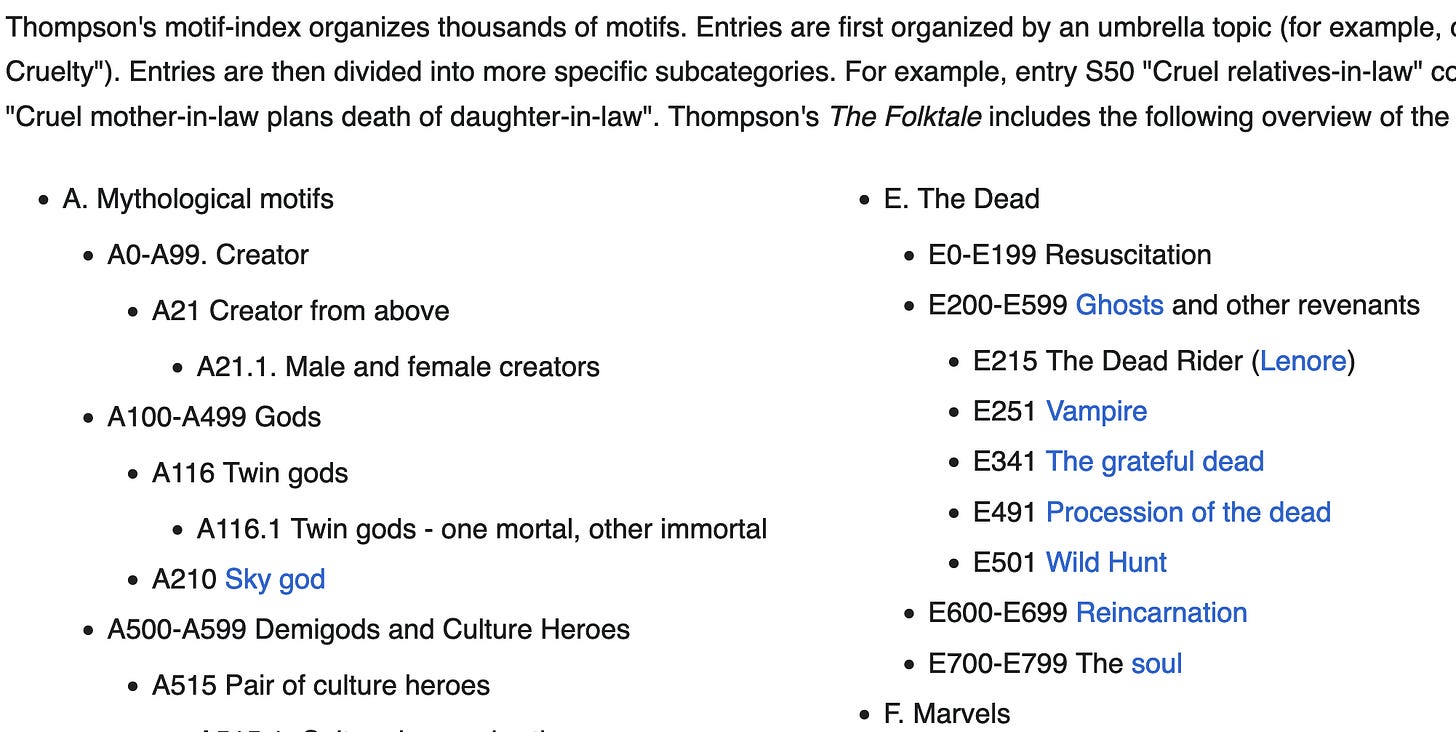

After stepping down a level to the elements of language, called phonemes, folklore stepped up a level from words to stories, songs, jokes, images. People began to catalogue and compare not just the work of famous artists, but the entire outputs of whole cultures. They discovered a level in between, story elements they called motifs,

which today we would call tropes or memes, clusters of meaning that could vary across stories and cultures (like my boarish digression above) while still being recognizably alike. I wrote an article about the history of memetics for IGMS a few years ago called Spelunking the Noosphere.

In 1976, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins hypothesized a unit of information that he called a meme, a unit of information that could copy itself. He called them replicators to emphasize their agency, despite knowing perfectly well that genes do not in fact copy themselves in any literal way.

That’s the background and framing for a neat little article from Smithsonian Folkways called The Folkloric Roots of the QAnon Conspiracy.

There we can find, for instance, motifs that reference child abduction (R10.3), child sacrifice (S260.1.1), and killing children for their blood (V361)—all of which help to explain why the legend known as the blood libel remains so persistent.

In other words, every single element of that memetic mess is borrowed from somewhere else and recombined into frothy new forms, the flotsam and jetsam of the rising and falling tides of culture. Bellingcat did a series on it, including an origins piece that details the previous insider LARPs that immediately preceded it.

Artists are more skilled at this process, but we all do it, day and night, waking and dreaming. The endless and effortless recombination of words into sentences according to the rules of grammar and syntax is just the most obvious expression of the dynamic. If you ever meditate for an extended period of time, you’ll find images, memories, emotions, even bodily sensations repeating in loops. The frequencies and intensities vary, and are interrupted by external events, but we all have consistent patterns.

It is certainly possible to study this stuff scientifically, in a third-person objective way, by summarizing polls

or by profiling individuals who have gone so far as to commit crimes.

This project seeks to advance the study of bias crimes by building on the lessons we have learned from a series of NIJ-funded projects called Profiles of Individual Radicalization (PIRUS). Based on the PIRUS model our research team will construct a database of 1,000 convicted bias crime offenders that is both national in scope and representative of multiple offender types. The dataset will include detailed information on offender demographics, socioeconomic measures, social relationships, and other life-course variables that may contribute to the formation of hate beliefs and the commission of bias crimes.

Pathway analysis is really interesting, and I could go into more detail on that.

And then there’s the humanistic case study approach used by reporter Jessalyn Cook in The Quiet Damage, following five families as they disintegrate, which is probably more valuable for the general public’s understanding.

Charting the arc of each believer’s path from their first intersection with conspiracy theories to the depths of their cultish conviction, to—in some cases—their rejection of disinformation and the mending of fractured relationships, Cook offers a rare, intimate look into the psychology of how and why ordinary people come to believe the unbelievable.

I’m sure I will get to that book at some point, since my wife is reading it, but this weekend, home sick with a head cold of some sort, all I can manage is tracing sketches off my laptop screen while Frontline plays in the background.

All of this is in preparation for our first Pyrite serial, which I have never been able to completely settle on a title for:

The Lizard Thing?

The Lizard Sting?

The Wizard’s Bling?

Seeya next week, unless this cold turns out to be lycanthropy12.

https://www.themonstersknow.com/lycanthrope-tactics/

I would definitely be a werewolf.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red:_Werewolf_Hunter

I love Felicia Day, but this was a terrible movie.

Totally coincidentally, two other Substack authors are doing a much deeper dive on "On Fairy Stories" this fall.

https://ericfalden.substack.com/p/tolkiens-on-fairy-stories-the-art

https://lorddarcy.fandom.com/wiki/The_Muddle_of_the_Woad

I have one of the 3-in-1 volumes, pictured in this overview from Black Gate.

https://www.blackgate.com/2022/10/09/vintage-treasures/

This describes author Randall Garrett as "An unrepentant fan of puns (once defining a pun as 'the odor given off by a decaying mind')"

https://thrillingdetective.com/2021/02/01/lord-darcy/