First a pair of quick plugs. Winston Malone at Storyletter XPress has once again taken leave of his senses and published another multiply rejected story of mine,

and the grind of self-promotion continues with a paid contest for free advertising (???).

Seems like it would be simpler to just pay for advertising, but what do I know? I’m clearly very bad at selling things.

A recent post on Astral Codex Ten reminded me of two inflection points in my “career.”

Spring 1991

This was my junior year of undergrad. I was simultaneously taking Animal Physiology, a 300-level course, and a Zoology seminar, 523, which turned out to be mean Read a bunch of research papers and present on them, what I would later call a literature review when I briefly ran A&T’s senior projects course.

I do actually keep a copy of both my college and graduate transcripts around, because some employers (mostly academics) want to see them. Checking the undergrad one, I was surprised to learn that I took both of those courses at the same time. The way I remembered it, I had the same professor for both: a guy named Crawford who did a lot of cool stuff, including (according to campus folklore) following wild ostriches around Africa with a rectal thermometer. In my personal folklore, I took Animal Phys, was impressed by him, and took a second course with him1. Of course, records are not perfect, either. His obituary states that he retired the year before, in 1990.

I loved Animal Physiology, which is where the previous hints about feedback regulation in other courses were really explored in detail for the first time. I thought the countercurrent mechanism in the kidney was one of the most aesthetically beautiful things that I had ever seen.

I was thinking a lot about beauty at that time, probably in part because I was taking English Lit II, which is where you meet the Romantics. I was especially impressed by William Blake, who was both a writer and a visual artist. Not that I especially liked or agreed with his work in either area. It was more the fact that he was able to do both things successfully and be recognized for them.

Anyway, it was that lit-review course that came to mind. Not because of the ACX article’s call-out to the Gila Monster, a desert lizard whose venom provided the first version of the blockbuster weight loss drug, triggering memories of Crawford (though he did also study lizards, and frogs, and dogs). No, it was because my project was on weight control in mammals.

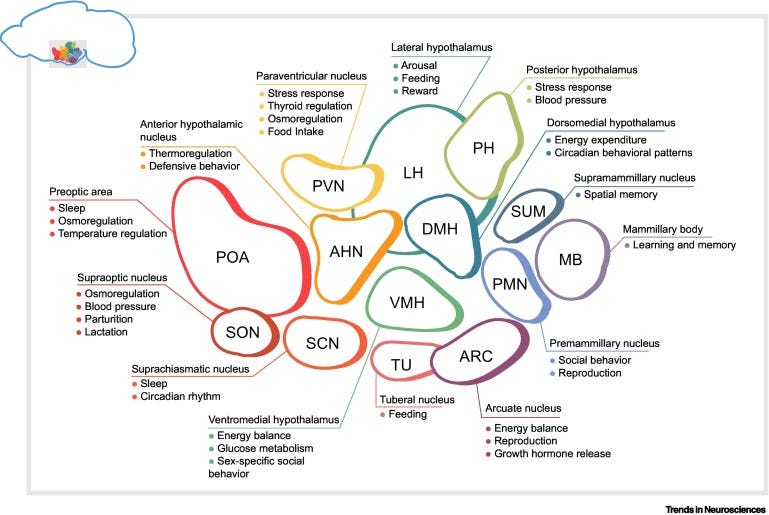

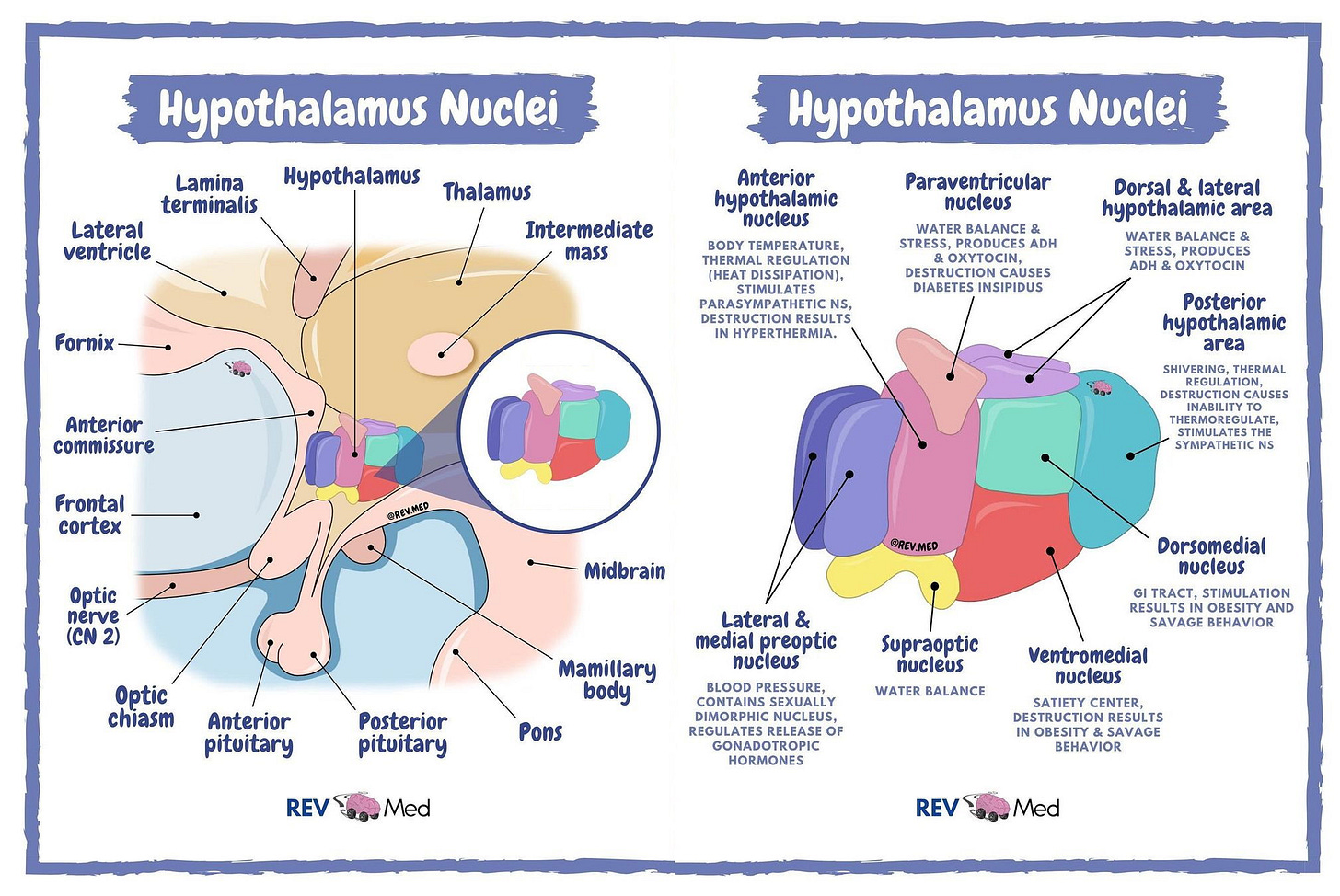

This was back in the days before we had gene knockouts or mRNA silencing or any of those technologies. Mostly what they were doing was comparing hibernating animals (who gain a lot of weight all at once, seasonally, and then lose it again) with non-hibernating ones, to see what differences they could find. Or comparing the hibernating mammals when they were in their weight-gain and weight-loss phases. Then they would damage (“lesion”) tiny areas of the hypothalamus to try and flip animals who were in one state to the other.

The hypothalamus is really old, in evolutionary terms, and devilishly complicated. Sometimes it seems like every individual cell does something unique.

Recently, single-cell RNA sequencing technologies have uncovered new and functionally distinct neuronal subtypes in the hypothalamus. Studies have also revealed significant transcriptional and functional heterogeneity among cell types previously thought to be homogeneous.

It was those experiences that initially turned me on to neuroscience. The next summer I jumped into an undergrad research experience in an Alzheimer’s lab2.

Sometime in the 20-tweens

I started doing computational models during the 90s in grad school. My boss hated writing code and preferred to use LabView, a programming language that used graphical icons to generate lines of code, to control his monkey experiments. When to present the stimulus, when and how often to squirt fruit juice as a reward, that kind of thing. I got started using a scripting language called MatLab for working with stroke patients — I honestly do not remember why, other than that there were toolboxes for psychophysics3 whose functions made some sense to me. Probably the fact that I could start over, and start small, without having to grok an existing control network, had something to do with it.

By the time I started teaching it was clear to me that those tools were beyond the needs and interests (if not the abilities) of undergrads. I fell back on canned simulations from Jon Herron and others, because they were simple and free. I also used an earlier version of the Fractal Terrains demo in my Alien Ecosystems exercises. As an adjunct I couldn’t buy things for my students, and I couldn’t force them to buy them for themselves.

Then I found Nicky Case. Nicky is prolific. That site has dozens of cool little demos and toys that I have used with my neuroscience students over the years. My favorite, though, the one I come back to over and over, is LOOPY.

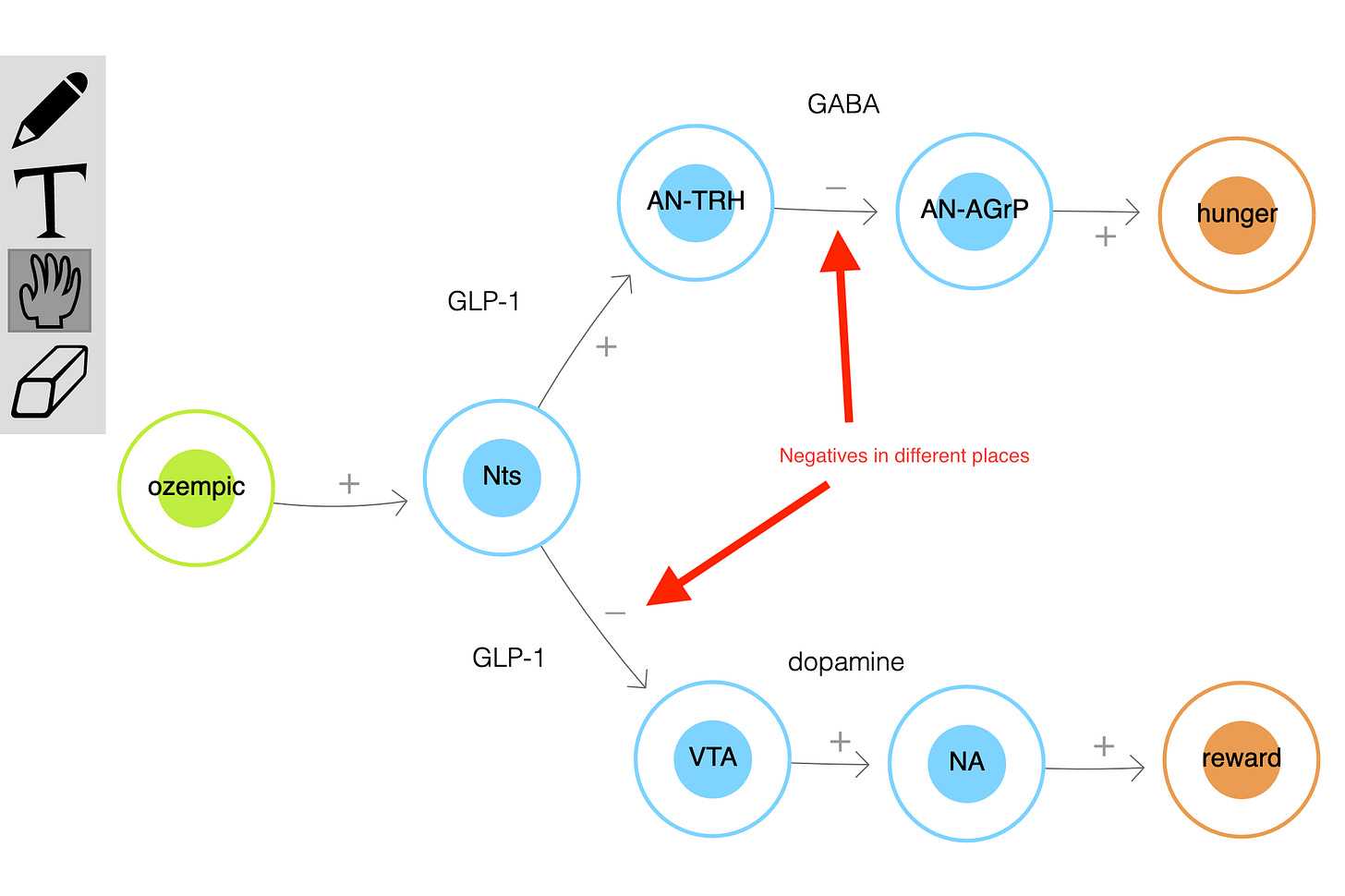

LOOPY has a super-simple sketch-like interface where you can take a model diagram like this one from the ACX blog post

and make it interactive. With a simple one-way model like this one (no loops), this might not seem worth it. Yes, you can see that it doesn’t matter where you place the sign reversal, as long as there are the same number of them. That’s sort of trivial, but it’s also the kind of thing that students don’t necessarily think of for themselves.

That’s the real beauty of this approach. It turns a flat, static, received-wisdom diagram into a tiny little laboratory. Passive can become active. I can have a group of students turn a graphic from a journal article into a LOOPY model in about five minutes. Then they can start interrogating the model for themselves. This is incredibly powerful, as a learning tool.

(Quick plug: sometime ACX contributor Brandon Hendrickson writes about this kind of educational stuff all the time.)

One of the best parts about LOOPY from an educator’s point of view is that, unlike most modeling systems, the numbers are hidden under the hood. Having only 7 possible values in each circle is limiting but also freeing. The majority of the college students I meet (including many STEM majors) hate mathematics and avoid numbers as though they were actually dangerous contagious things. They think of math as a topic and not a tool (because that’s how they’re taught). They don’t estimate in their heads before they calculate with their phones. This leaves them prone to accept whatever answer the calculator magically gives them, without checking it to see if it makes sense.

Should my answer / output be larger or smaller than my inputs?

A lot of what I’m doing in my lab classes is actually the same thing I’m doing in my neuro classes. It’s applied mindfulness — trying to get students to think about the process of thinking, about how they experience things, how they interpret things, and giving them better tools so that they can think better.

Not faster. Faster is usually worse, at least at first. I’m tempted to go with a Yoda quote here but I’ll resist that temptation, because we’re already over the e-mail length limit.

Next week, we return to On the Brink of Utopia to talk about the Sith . . . um, I mean . . . innovators!

There are two other courses on that transcript in the spring of my senior year: Bio 522, Independent Study in Zoology; and Psy 558, Biology of Motivation, that I have no memory of at all. Maybe one of those was a Crawford repeat?

which did not go well. Someday I will write it up as a comedy of errors (all mine).

tl;dr version

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/ozempics-surprising-real-power/

I never saw ROOTS and I never watched a single episode of READING RAINBOW. I knew Levar Burton only as Geordi LaForge from STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION. But the title of the RR episode "Gila Monsters Meet You at the Airport" struck me as funny, because of today's topic.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt15358498/