Last summer I went to science and engineering honor society Sigma Xi’s Science Policy Bootcamp, which will happen again this coming July, for those interested. My quick report on that experience is below.

The person that I asked to do this week’s Q&A, who I met through that event, said no thanks, in part for fear of offending the wrong people.

Given that over 300 students have already had their visas revoked, I can’t say I blame that person. That seems to be where we’re at, as a society.

As a Lecturer on a one-year contract, maybe I should be scared myself. Maybe I’m just dumb. But I’ve been fired before1, and I’m here to tell you that in my personal experience, there are worse things than being out of white-collar work in a prosperous society. Life is short, and at fifty-four years old, I do not have time to be afraid of middle managers.

I also don’t have time for sugar-coating things. At the Newcomers’ School Career Day this past week, students heard that they could start at $50k in the Merchant Marine, after only two months’ training, and work their way up to the mid-to-high six figures. I spent four years in undergrad, seven years in grad school, plus another two years as a postdoc, and I still don’t make $50k2. I told them this openly. Let them make up their own adolescent minds.

But, then, I grew up on a farm, where we routinely recycled our used motor oil into barn paint3, so my personal definition of abundance is probably out of step with your average American consumer’s.4

Science Fiction and Science Policy

I’ve written about these issues multiple times, starting in 2017 for the Intergalactic Medicine Show, in a piece called “Saving the World for Six Cents a Word”.

There are examples of SF authors being involved in policy at a surprisingly high level. According to this interview with Karl Schroeder5, the Canadian military has been working with writers off and on for a hundred years. Arthur C. Clarke had a long-term relationship with NASA and apparently everyone else, too. Isaac Asimov told DARPA how to be creative. There’s a current group called SIGMA, involving about forty of SF’s heavier hitters6. And Ted Halstead's New America think tank sponsored the Heiroglyph anthology, as well as a column in Slate and an ongoing series of Washington events with techies and policy wonks.

A link to one of those more recent events (online) was posted to LinkedIn by Nic diPalma of Breaking Futures here on Substack. Oddly, the first 15:42 of the video is just a loop of some slides. There’s also a glitch in the audio from 21:24-29-21, so unless you can read lips . . . )

Highlights for me:

Cole Donovan pointing out that more science fiction means both better and worse science fiction (the Bell curve just gets broader, y’all).

Will Hurd talking about AI giving him more time to play with his daughter, which is not edgy and Twitter-y, but which was exactly what my first published story was about, in part.

Ed Finn’s idea of k-12 Futures classes, comparable to our current k-12 History classes, and giving people permission to dream actively themselves, not just passively absorb others’ information and stories.

There was also a link to an article by Ed Finn, who runs Arizona State’s Center for Science & the Imagination.7

We’ll never get to those better futures if we don’t imagine them first. And while science fiction has given society plenty of cautionary tales and dystopian classics to choose from—yardsticks we can use to measure against the futures we don’t want—we have very few protopian8 yardsticks we can use to measure our progress toward a better future for all.

There are many ways to bring science and science fiction into dialogue. Our preferred method at CSI is to host structured workshops where participants from diverse perspectives work together to collaboratively imagine a future using creative exercises and tools, collectively described as worldbuilding.

This is essentially what I’m doing at a lower level with my Alien Ecosystems students. The goal in my case is less to solve a specific problem than to give them practice at problem-solving in a fun and compelling way. Practice with imagination may be just as important. Finn references a study of UN experts who couldn’t (or wouldn’t) imagine victory conditions outside their silos.

If those who are best informed about the real context and possibilities of the human response to the climate crisis cannot imagine what our future should actually look and feel like, how can the rest of us do it?

Maybe even more important.

An Evening with Jeff Vandermeer

One of our class field trips was to the Carolina Theatre downtown, where the Greensboro Bound book festival had recruited the guy who wrote Annihilation, which was soon made into a movie with Natalie Portman.

I had previously made it through probably the first third of the movie with my kid. It was late; I went to bed. The kid stayed up through the whole thing and (being much more of a horror person than I am) really enjoyed it, enough to read the first book.

In the clip, Natalie Portman’s character says of Area X, “It’s not destroying . . . it’s making something new,” as though that’s not what evolution is always doing, admittedly a bit more slowly. In my jaded nerd-mind, I equated it with the protomolecule from The Expanse and let it go at that.

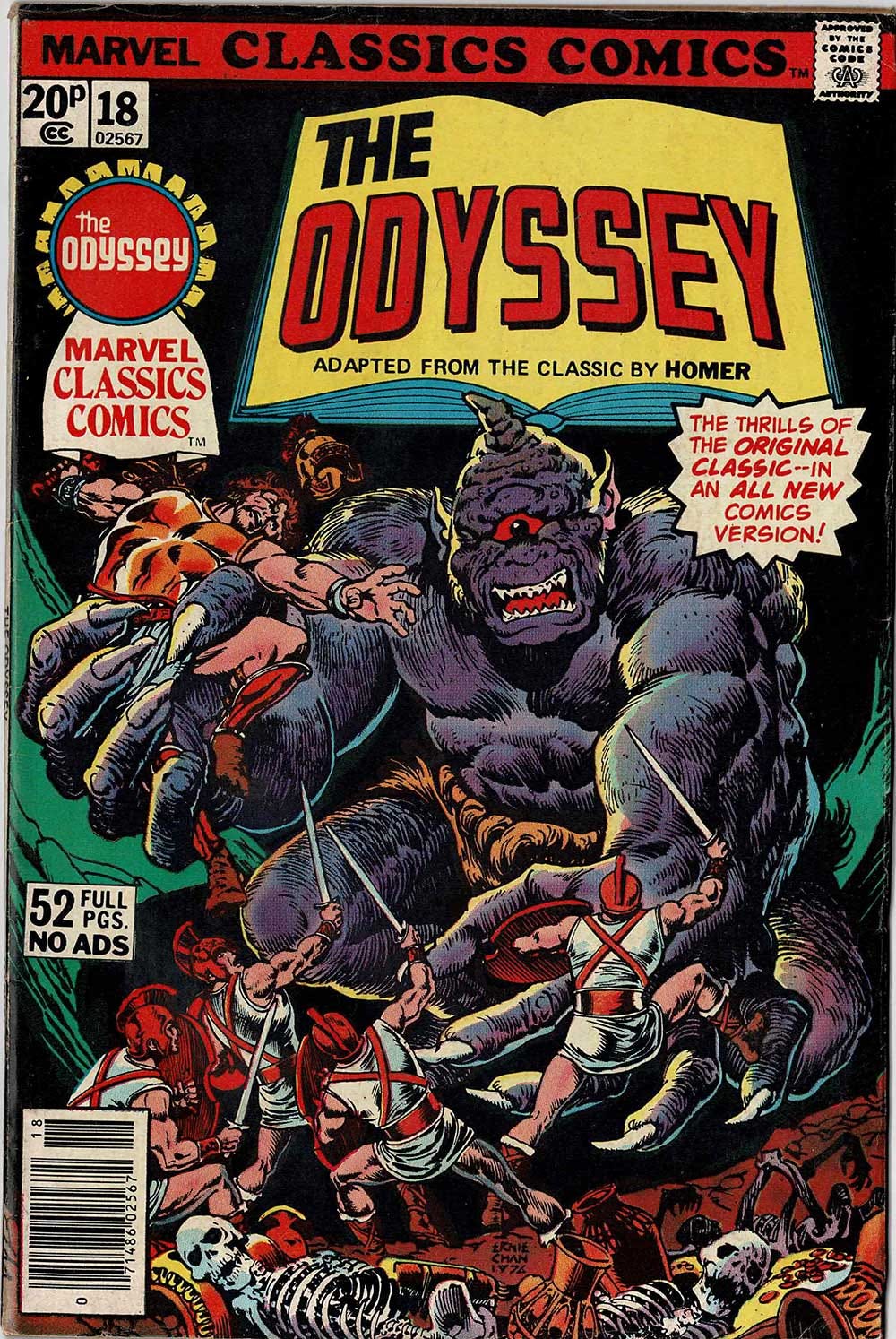

Because these days I mostly read short fiction, I knew Jeff Vandermeer more from his editing work. He and his wife Anne did The Big Book of Science Fiction, a 1200-page monster with over a hundred stories spanning roughly a hundred years in the history of the genre. SF was once avant-garde literature (respected intellectual and activist WEB DuBois wrote “The Comet,” an interracial Adam & Eve story, pretty daring for 1920)9, before it became pulp entertainment for the masses.

It was a pretty standard Who are you, and where do you get all your crazy ideas? kind of interview, with some time reserved for fans to ask about their own more personal obsessions. There were 50+ people there, I would guess — not bad for a Thursday night in Greensboro.

SF is sometimes thought of as idea porn, where the cool tech or the cool idea is the important part. Which it is, but as Ed Finn says in his article:

Science fiction is a free, infinite laboratory of the mind that allows its audience to envision possible futures in context. By centering characters—people—instead of technologies, writers have to offer concrete answers to those nagging questions which can be so easy to gloss over when an invention or discovery exists only as a concept. Who will own it, use it, pay for it, maintain it? Where will it be installed or deployed? What does it look like, smell like, feel like? How does it actually work? Does it need to be plugged in? What if you drop a piece of toast into it? What else must be true in the future for this thing to exist? These questions create what I call speculative specificity: The craft of effective storytelling pushes authors and readers to play out second- and third-order consequences and to imagine the full context of a changed future.

Only two of my fifteen students were there, one in the back where I couldn’t see him. Later in class he was impressed by Jeff Vandermeer’s discussion of an unreliable narrator in one of the later books in that same Southern Reach series. It’s a pretty standard writerly tool at this point, but as a young person he was not surprisingly unfamiliar with the concept. This reminded me of a recent article by fellow Substacker

on authorial adviceand how so many of my students are constantly playing defense, hobbling themselves by trying never to be wrong (or more importantly, never to be seen being wrong). This is a more subtle and I feel like sometimes a more pernicious anxiety than being afraid you’ll lose your visa. I hate it, and I push back whenever anyone will listen to me. Last week I had the class read this older piece by another Substack author called

who says

I love these stories as tiny little microcosms of agency. none of them mean a whole lot. nothing done in them required any special talent or novel insight. none really affected the world in any meaningful way. just some kid learning by accident that things can happen because you decided to do them

How do we legislate that?

Keep your freak flag flying,

rh

Or just quietly not re-hired after the temp contract ran out. Remind me to tell you about the NC Governor’s School some time.

Though I did previously, for about six years, as an assistant professor.

My dad also used various petroleum products as animal medicines, which might have been fine for a huge animal like a cow, with a low surface area to volume ratio, but which worked out very badly for my favorite cat Ninja, who got the mange and then died from licking diesel fuel off its fur.

And possibly with this much-talked-about book’s as well. I’ll let you know when I finish it.

who is now writing one of my favorite Substacks, Unapocalyptic.

of a previous generation — all lily white, mostly male, and some (like Jerry Pournelle) dead.

Just one article of a whole issue on our scientific and political moment.

https://issues.org/issue/41-2/

including a remembrance of Lewis Thomas, who wrote The Lives of a Cell, which I read between my junior and senior years of high school. I never knew that he was a medical doctor.

“Protopian” essentially means not necessarily good but getting better.

Oh, I guess we're up to 1000 now.

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/global/international-students-us/2025/04/07/where-students-have-had-their-visas-revoked

For those TLDR foks, here's the podcast interview version of ABUNDANCE,

https://www.theatlantic.com/podcasts/archive/2025/03/derek-thompson-and-ezra-klein-abundance/682077/

which I read in transcript form, just to be spiteful.