Experiential Neuroscience 2023

Durham co-ed edition

For the first time in ten years, I am not teaching during the summer. This has allowed me to do other things:

clean out the attic;

clean out the gutters (and replace the filters that got destroyed when we replaced the roof last year);

spend more time in the yarden (more on that soon);

submit a bunch of stories and articles (mostly re-submissions of old stuff to new magazines);

sign up to take a class myself.

That’s Right, 2023

I’m not sure why I never got around to posting a description of my second class for Science & Math last summer.

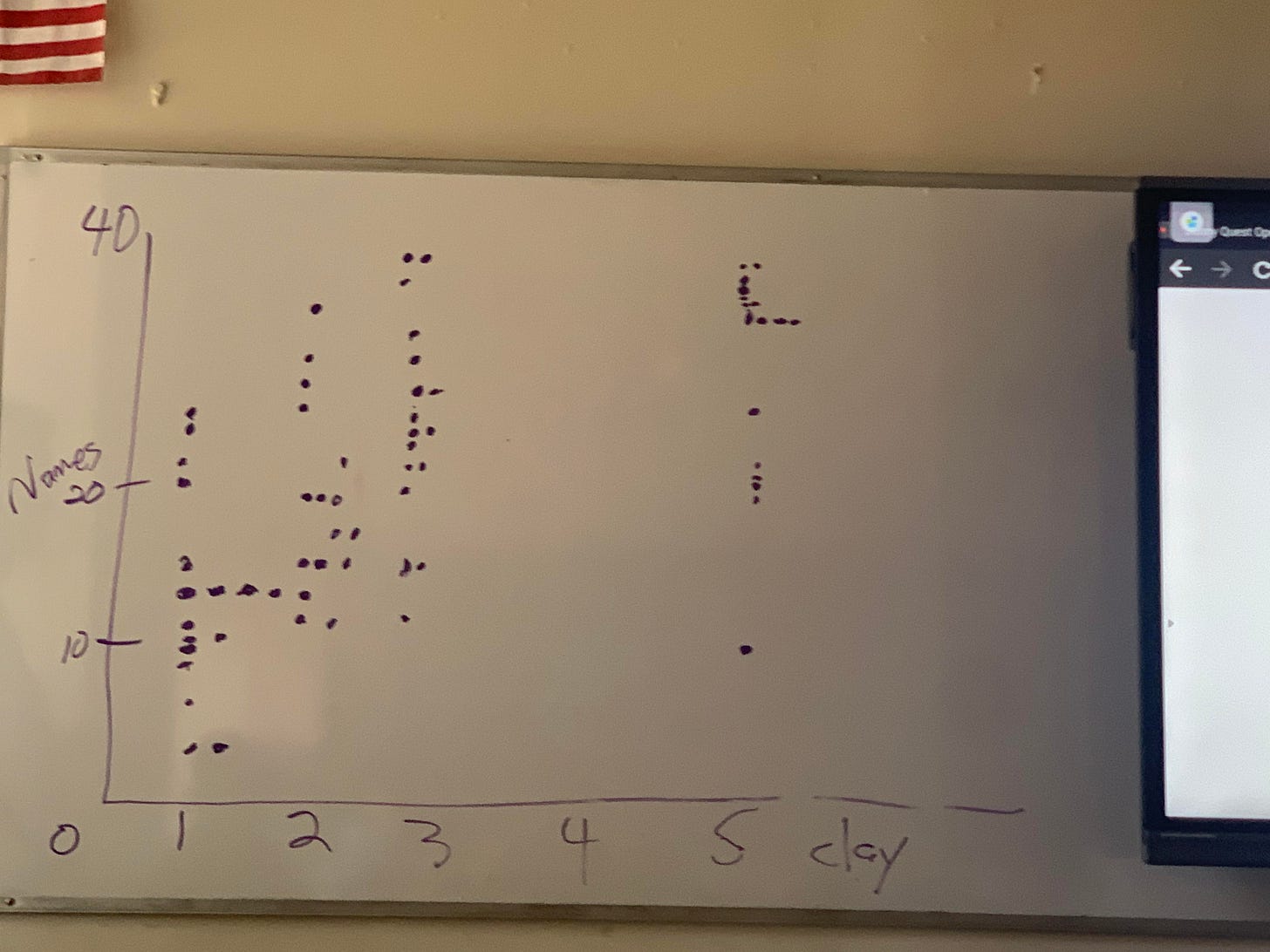

I always do an icebreaker where after the students introduce themselves, I make them write down all of the names they just heard. Then we make a dot plot on the board. This serves several purposes:

It gently calls out those who were not paying attention.

It sets a clear expectation that everything that happens in our orbit is fair game for discussion (but not without some judgement; see below).

It expands science outside the lab and the classroom into everyday life.

It opens into a concrete discussion of what types of information people are using (faces, locations, voices, sequences) and where and how the brain combines those different channels.

Then, the next day I surprise them again by repeating the experiment and showing that they learned (a little) without actively trying. Names are so important to our normal social interaction that we use them a lot. Sleep is also super-important for consolidating short-term memories into long-term memories, or at least sleep deprivation is highly disruptive to that consolidation process.

Y’know, like during a summer camp, away from your parents.

This class ran for two weeks online before our first in-person meeting, so they did better with the names than most of my college classes do on the first day. Most undergrads score less than ten on the first try, where here the mode was 12 or 13 (with first and last names counting 1 point each). Also notice how even by the last day, when the mode had tripled to 30+, there was that one lonely point down about 10 or 11. Humans vary, and sometimes they vary on purpose, refusing to engage with a particular task for social reasons. I’m sure you’ve seen examples.

A higher percentage of these kids were making noises about careers in STEM than those in my previous Introduction to Permaculture class, even after being deluged with short science talks over Zoom by the grad students from Robert Hampson’s science communication class at Wake Forest. The next day we had a shorter Zoom with Andrea Salazar of the Brain Awareness Council, who hopes to do science outreach full-time “at a museum or something.”

And then we read this, which invites us all to contribute to science in whatever way we like, recognizing that good science is hard to do (even for professionals).

I happen to disagree with Adam’s dislike for the phrase “citizen science,” because I think there is a useful distinction to be made between people who are paid to do something (like a politician) and people who are not (citizens). There’s a higher standard for professionals, and there should be. I’ve been teaching pre-meds for a long time. Some of my students are people who I personally don’t want in charge of any aspect of my health.

Out of the Frying Pan . . .

We got deeper into addiction than in any other class I’ve done recently. These kids are far too young to remember the major public health campaigns of the 1980s, the very effective “give me your keys” campaign by Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and the more memorable but less effective “your brain on drugs” campaign.

I pretty much always point students towards Stuart McMillen’s Rat Park comic. But this year we also talked about the Drug War, especially how the 60s panic over psychedelics played into it and set back the research by almost 40 years. MDMA and psilocybin will finally be approved by the FDA for multiple therapeutic uses within the next five years. I hope.

We ate apple cider doughnuts from Monuts (which are crusty with sugar) to mindfully experience the sugar high — and then the crash. Results varied, but some people began to notice changes within 7-8 minutes.

The difference between normal reward and addiction is a slippery issue that is still being actively debated in the scientific literature. Science is conservative. Individual anecdotal experience is almost by definition way out in front.

Let me know if you want me to dig into this in more detail.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Doctor Eclectic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.