Adventures in Permaculture

just what the hell is that, anyway?

Hey, y’all. This is one of an occasional series where I write about permaculture, which is basically an attempt to build and manage human systems in ways that mimic natural ecosystems. There’s a lot of theory behind that simple phrase, embodied in a set of principles. Sometimes there are ten, sometimes eleven or twelve.

Observe and interact: Take time to engage with nature to design solutions that suit a particular situation.

Catch and store energy: Develop systems that collect resources at peak abundance for use in times of need.

Obtain a yield: Emphasize projects that generate meaningful rewards.

Apply self-regulation and accept feedback: Discourage inappropriate activity to ensure that systems function well.

Use and value renewable resources and services: Make the best use of nature's abundance: reduce consumption and dependence on non-renewable resources.

Produce no waste: Value and employ all available resources: waste nothing.

Design from patterns to details: Observe patterns in nature and society and use them to inform designs, later adding details.

Integrate rather than segregate: Proper designs allow relationships to develop between design elements, allowing them to work together to support each other.

Use small and slow solutions: Small and slow systems are easier to maintain, make better use of local resources, and produce more sustainable outcomes.

Use and value diversity: Diversity reduces system-level vulnerability to threats and fully exploits its environment.

Use edges and value the marginal: The border between things is where the most interesting events take place. These are often the system's most valuable, diverse, and productive elements.

Creatively use and respond to change: A positive impact on inevitable change comes from careful observation, followed by well-timed intervention.

Notice how you could apply these principles to any system — a school, a business, a town — not just a farm or a garden. The point is that all our systems are in fact natural systems, whether we acknowledge them as such or not. Culture is smaller than nature, not larger. Culture does not accept this, and culture is mistaken, which is why cultures collapse. There’s nothing outside of nature.

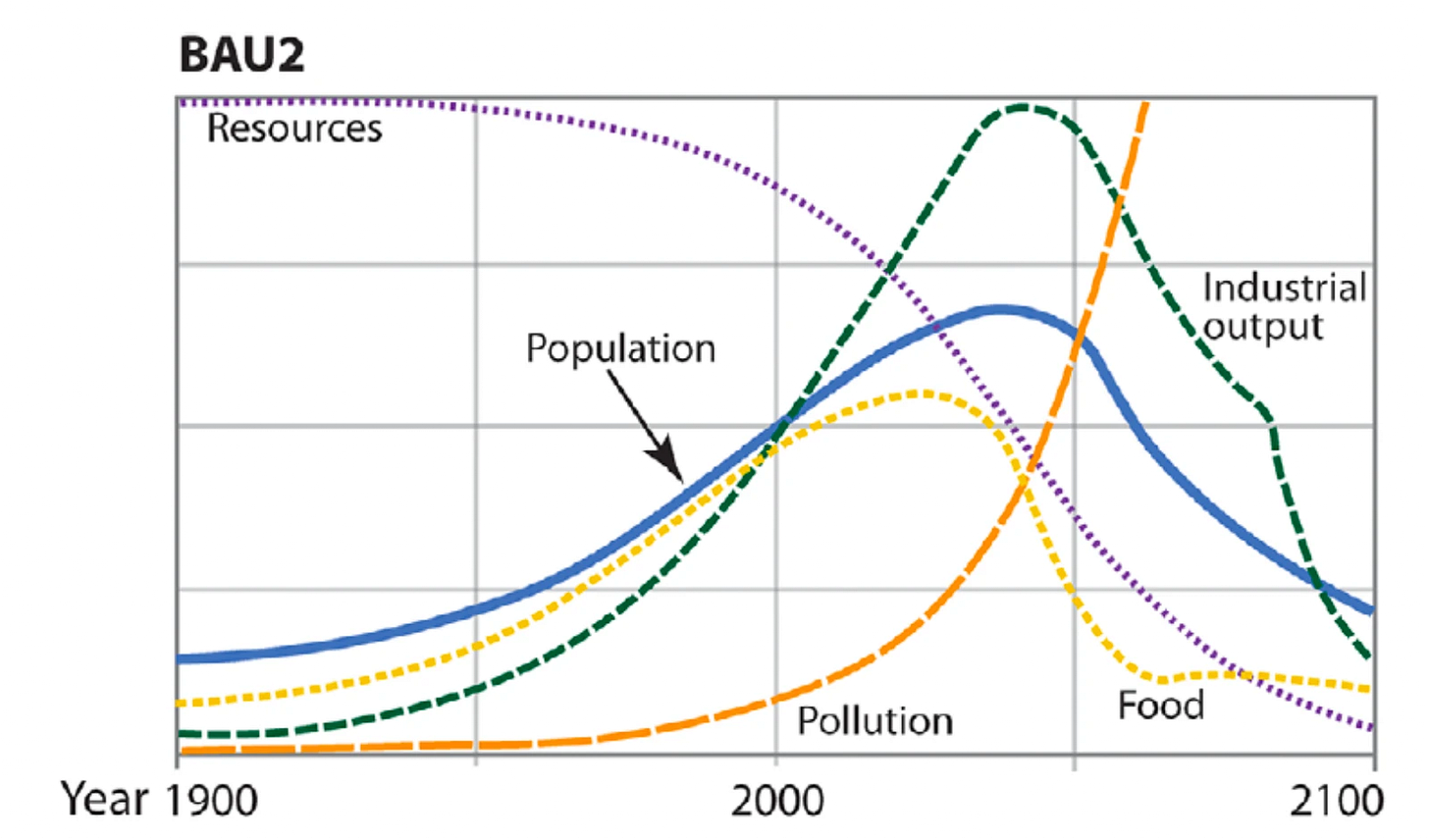

A remarkable new study by a director at one of the largest accounting firms in the world has found that a famous, decades-old warning from MIT about the risk of industrial civilization collapsing appears to be accurate based on new empirical data.

This is not science fiction. These are corporate accountants telling us that we need to change our priorities. Look at that blue line. That blue line represents billions of human deaths, mostly through starvation as the food supply (the dotted yellow line) collapses.

Meanwhile, my wife calls to tell me that we need a new roof, or the insurance company is going to drop our coverage. Essentially, they’re trying to force us to contribute to the overall economic growth that is killing us in slow motion.

The report makes sure to say that we do still have time to turn this around, and cites the worldwide emergency response to COVID as evidence that we can in fact do big, coordinated projects if we just choose to do so. As further evidence I would include the Victory Garden movement, which during World War 2 had US cities growing close to 40% of the nation’s fresh vegetables.

My Personal Efforts to Preserve My Little Corner of the Planet

I’ve been a member of the Greensboro Permaculture Guild for years. I did manual labor on many of their projects,

the Deep Roots Forest Garden (Eugene near Smith Street)

the Giving Back Garden of the First Presbyterian Church, (corner of Fisher & Simpson St)

the public orchard at the Meeting Place, (corner of Smith and Prescott on the Greenway).

Greensboro Montessori School gardens (2856 Horsepen Creek Road)

and eventually got my design certification in a class with Jenny Kimmel.

That has led me over time to make some efforts to spread that message, including to high school and college students.

“Introduction to Permaculture” at NCSSM

The class I did for Science & Math this past summer involved 2 weeks online, where the students spent about ten hours re-designing their own home properties on paper. When they came to campus, we surveyed the small but diverse pocket gardens clustered between the buildings, identifying native and non-native plants, and did a preliminary experiment, spraying yogurt bacteria on several different trees to see what it would do to their fungal infections. The campus compost pile went away during COVID or we’d have made compost tea.

We also did walking tours of the residential neighborhood, to examine as many different designs as we could — purely ornamental, edibles, more focused on wildlife. We compared and contrasted. What were the most common plants? Where were they from? It turns out many of our ornamentals, like the crape myrtles that were blooming so aggressively at the time, are non-natives from Asia or Australia, planted for the precise reason that they bloom out of synch with our native plants, and because almost nothing here eats them.

That might not sound like a problem, but if insects can’t find plant food, then baby birds starve. Unlike adults, who can eat seeds and berries, fledglings need huge amounts of protein to grow their flight feathers, so they eat essentially nothing but creepy-crawly invertebrates (insects, spiders, slugs, etc). I first learned this about ten years ago from a lecture at out local Audubon Society, based on a book by Doug Tallamy, who now runs a nonprofit group called Homegrown National Park.

In the past, we have asked one thing of our gardens: that they be pretty.

Now they have to support life, sequester carbon, feed pollinators and manage water.

— Doug Tallamy

Ironically, permaculture has always been more centered on growing food for people over wildlife, but I see the two approaches as highly compatible, and that’s how I teach the course.

Also, because it’s Science & Math, the population they’re drawing from is at the very least nerd-adjacent, so I wrangled us a field trip to a local biotech company called Oerth Bio. For those of you whose Greyhawk antennae just went up, yes, you are correct. All of the names of their lab and conference rooms were D&D references, and one of their lab refrigerators was named Frodo.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Doctor Eclectic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.